Fiber artists tackle difficult subjects in QAQ 2020

At first glance, Jeanne Hewell-Chambers’ quilt “Playground of Her Soul” looks like a fun, child-like piece with its brightly colored squiggles sewn onto a black background and a size 3T white pinafore sewn onto the center. But the atmosphere changes when you read the text sewn onto the dress.

“When she was 3 years old, teenage boys made my sister-in-law Nancy part of their game of Cowboys and Indians by hanging her with a rope from the swing set,” it reads. Nancy was never the same, Hewell-Chambers said.

“Nancy was severely impacted by this tragedy,” she said, noting that Nancy, now 61 and living in a special home in central Florida, has a limited vocabulary of about 12 words. “She needs help with everything – feeding herself, toileting, dressing, going to and getting out of bed – everything. And through it all she smiles.”

Hewell-Chambers’ intensely personal artwork is one of 71 art quilts featured in the Schweinfurth Art Center’s “Quilts=Art=Quilts 2020” exhibition. The show, which includes artwork from 26 U.S. states and five other countries, is on display from Oct. 15, 2020, to Jan. 10, 2021, at the art center in Auburn. Several other quilts reference personal stories or heart-felt reactions to news events.

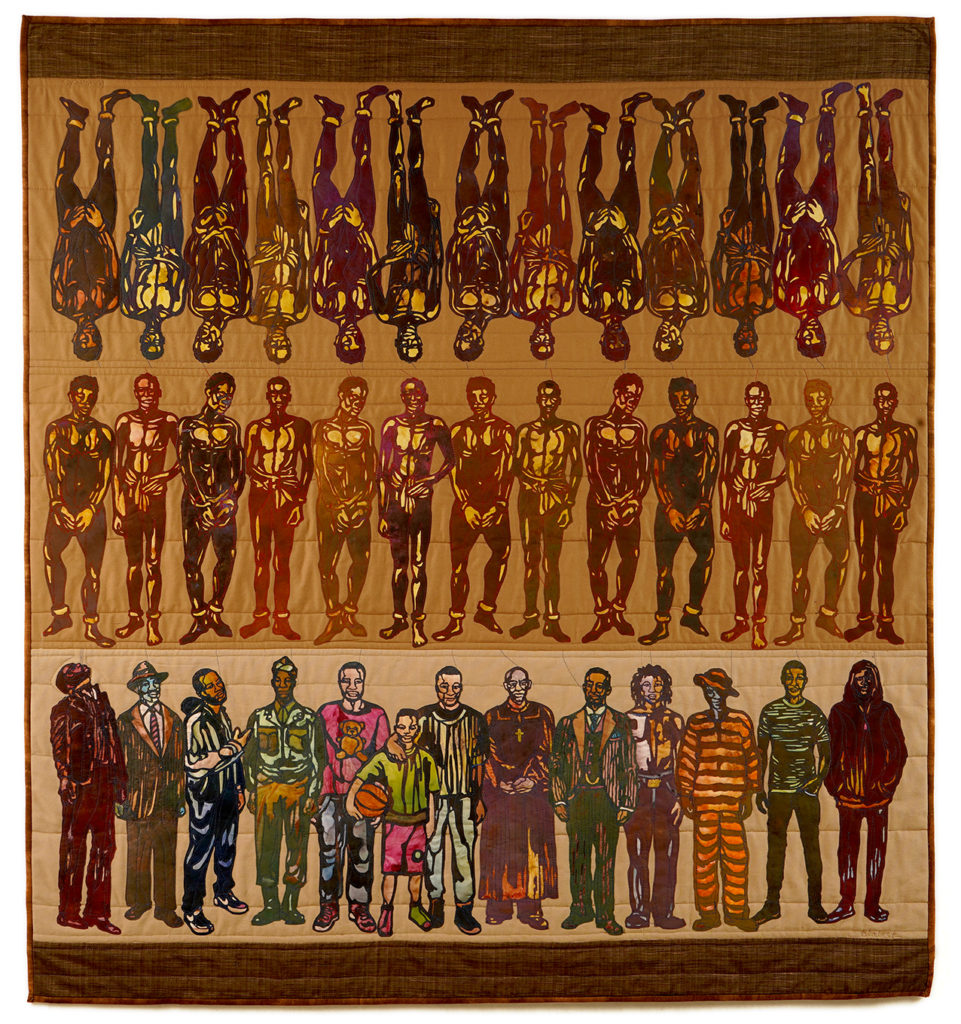

Of slavery and children

Consider, for example, Syracuse, NY, artist Ellen Blalock’s piece, “Middle Passage: America’s Legacy.” The figurative quilt shows three rows of black men, with the top two drawn from a history textbook image of how African men were packed into ships and transported to the United States to become slaves.

“Now, not centuries but a few generations removed from slavery, we continue to fight for human rights for all Americans,” Blalock said in her artist’s statement. “That is why BLACK LIVES MATTER. Because African Americans can still get killed, harmed, arrested while driving while Black, walking while Black, jogging while Black, birdwatching while Black, living while Black.”

The final row of people on the artwork represent the living legacy of the enslaved and includes portraits of Blalock’s father, son, and three nephews.

Another intense piece is by Candace Hackett Shively of Fayetteville, GA: “Unsafe, Unseen, Unheard,” made in 2018. The artwork shows several small hands – children’s hands – reaching through fences that remind one of the striped clothing worth by prisoners in German concentration camps and wild, jagged sewing that resembles barbed wire.

“What about the children?” Shively asks in her artist’s statement. “They hide in silence. They withdraw in fear from bombings, hide in camps among surviving relatives, mourn lost parents, or even drown – to be washed ashore as unidentified bodies. In the cruelest twist, children are torn from their parents’ arms and caged in solitary, terrified darkness, living a trauma they will never outgrow or comprehend.”

Soothing restlessness

Hewell-Chambers, who lives in Cashiers, NC, began sewing her sister-in-law’s drawings in June 2012, coincidentally 50 years to the day of the hanging. “A friend of mine and I visited Nancy for her first-ever all-girls weekend,” she said. “With no brothers or parents around, the three of us kicked off the weekend just how you’re expect: by ordering hot fudge sundaes and milkshake chasers.”

Nancy began to get fidgety while waiting, so Hewell-Chambers gave Nancy her journal and pen to distract her. “To my great surprise, she picked up the purple felt tip pen and started making marks on the paper,” she recalled. “By the time we left the restaurant, I had 167 drawings in what would become set one of the In Our Own Language series. I started stitching them that very night.”

Every time she visits Nancy, she leaves several reams of paper for Nancy to draw on. Nancy’s caregivers save the drawings, which Hewell-Chambers scans in, organizes, and stores the originals in archival quality page protectors and boxes. “Once that’s done, I stitch every drawing in a set, and the finished piece becomes part of the In Our Own Language series,” she added.

Since she began stitching Nancy’s drawings, the two have become closer. “Nancy’s highest praise is ‘pretty good,’ and now not only does her face light up when she sees me, she tells me repeatedly that I’m a ‘pretty good girl.’ And she never misses a chance to say ‘I lub you,’” Hewell-Chambers said.

In the eight years since Nancy first picked up that pen, her drawing has evolved and grown. “Her first drawings were curvy, childish marks,” Hewell-Chambers said. “Now she’s making color choices. I can tell they’re deliberate choices because she doesn’t scribble one color over another, instead stopping at a particular point and picking up a new color. And her drawings are more gestural with much movement. Her caregivers repeatedly tell me that since she began drawing, Nancy is much, much calmer.”

Healing through art

For Hewell-Chambers, reflecting on such a horrific incident is cathartic, especially for her husband. “It is satisfying and heartwarming for me because Nancy is so often overlooked,” she said. “Perhaps it’s more cathartic for my husband, Nancy’s brother, to bear witness to people responding with positivity and even admiration to the marks of his sister.”

She hopes that people who view “Playground of Her Soul” will realize that there are many ways to communicate and become more tolerant of people who look, sound, and speak differently. “Such is the power of art,” Hewell-Chambers said. “It touches places words can’t reach.”

Not all of the pieces in “Quilts=Art=Quilts 2020” are dark. Holly Cole, of Triangle, VA, submitted her piece, “Joy,” as an uplifting message she created in a year with a global pandemic.

“Sometimes you just need some joy,” she said in her artist’s statement. “During the pandemic, I thrived on stories of kindness, humor, and happiness, which directly shaped my studio work. This quilt is a celebration of all the stuff that’s still good for the soul, even in the worst of times.”

The Schweinfurth Art Center’s programs are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Gov. Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.