Artist explores erasure of Black history through her work

North Carolina native Quinn A. Hunter has always considered herself an artist. And she has always used her art to comment on issues she believed important.

“My work addresses what it means to carry the weight of 250+ years of being black into the 21st century,” she said, “how all of these external factors have led to the way I perceive, actively seek out, question, and struggle for reasoning with faith.”

Her upcoming exhibit at the Schweinfurth Art Center in Auburn, “Here/Hear,” includes work from two recent bodies of work that both focus on the erasure of Blacks in history. “Here/Hear” opens May 28 in the Schweinfurth Art Center’s second floor Davis Family Gallery and runs through Aug. 14. Hunter will be giving an Artist Talk about her work at 3 p.m. June 18, part of Auburn’s city-wide Juneteenth Celebration.

“Quinn’s work resonates with several topics that are important in our community today,” said Program Director Davana Robedee. “Her ‘Paradise’ series, documenting the communities erased in Detroit in order to build a highway, offers a direct parallel to the I-81 project in Syracuse. Each of her projects identifies how African American communities have been erased in the past – and how that erasure continues today.”

Early exposure to erasure

Hunter grew up surrounded by monuments to the Confederacy. In fourth grade, her class was shown the movie “Gone with the Wind” as an example of antebellum culture. As a student, she toured an antebellum plantation with her class where they were never told about the site’s history of enslaving people.

“I began to look at the way history is erased from our contemporary world. And the antebellum South became a strong reoccurrence,” she said. “Slaveholders and their descendants have been working to preserve and romanticize and sanitize the memory of the antebellum South ever since the end of the Civil War. They are actively working against history to rewrite and tell a story that discounts the horrors of the enslaved.”

That is what prompted Hunter to make the pieces in “I Hear You Now, I See You Then.” She chose three representative plantations: Nottoway, near White Castle, LA; Magnolia Plantation & Gardens, in Charleston, NC; and Twin Oaks, now known as Everhope, in Eutaw, AL. For each plantation, she created a chandelier and rug from African American hair weave and bits of Hunter’s hair that referenced actual pieces in the buildings.

“(Chandeliers and rugs) … showed a lot of monetary ability to purchase luxury goods, and such luxury goods were only able to be purchased through the enslaved labor of Africans,” Hunter said in an interview with Praxis Fiber Workshop.

‘Status and ambiance’

Magnolia, which grew rice, is one of the oldest plantations still standing, having weathered both the Revolutionary and Civil wars. As many as 235 enslaved people at a time worked the house, paddies, and gardens. Magnolia’s rug is sized to mimic the plantation’s dining room table and features rice plants as well as piles of rice. The chandelier Hunter replicated hangs in the plantation’s Carriage House.

“These chandeliers aren’t meant to provide light,” Hunter said. “They are more about status and ambiance.”

All three of the plantations rent themselves out as wedding venues. Magnolia is the only one that acknowledges its slavery past, both on its website and in person with an optional tour of former slave homes.

“These are sites that use erasure to profit from these places of historic pain.” Hunter said in her artist’s statement. “It is only through erasure that such a happy event can be held in a space of such grand historic pain.” She notes that there are plenty of plantations that promote their slave history, and don’t allow weddings because it.

Hunter is a performance artist, but the performance in these pieces were behind the scenes as she hand-pulled each strand of the hair into place. “I knew this project was going to be hard on my body, but I didn’t know how hard it would be,” she said, adding that she had to get help to complete the project because of repetitive stress injury to her hands. “For me, it was important that it was hand-done. My own physical labor re-inscribed the labor into the place.”

Destroying neighborhoods

Hunter’s more recent series, “Paradise: The Myth of a Liberal North,” focuses on the destruction of prominent Black neighborhoods in Detroit in the late 1950s and 1960s to build a highway. Hunter took on Detroit’s urban neighborhoods when she moved there to become artist-in-residence at Wayne State University. “I’m particularly looking at redlining and mapping Detroit’s history through redlining,” she said.

Redlining refers to a discriminatory practice that banks began in the 1930s to deny loans to people who lived in certain sections of cities deemed high risk. Those areas were marked in red on maps. However, those sections were often selected because of their racial composition rather than income level, which led to dilapidated buildings, lack of services, higher crime rates, and unemployment for residents since banks wouldn’t fund economic development in those communities.

With the growth of the national highway system in the 1950s and 1960s, these blighted neighborhoods were targets for planners and policy makers. In Detroit, as in Syracuse, NY, Black neighborhoods were demolished to make way for highways, obliterating the community’s wealth and tight-knit culture.

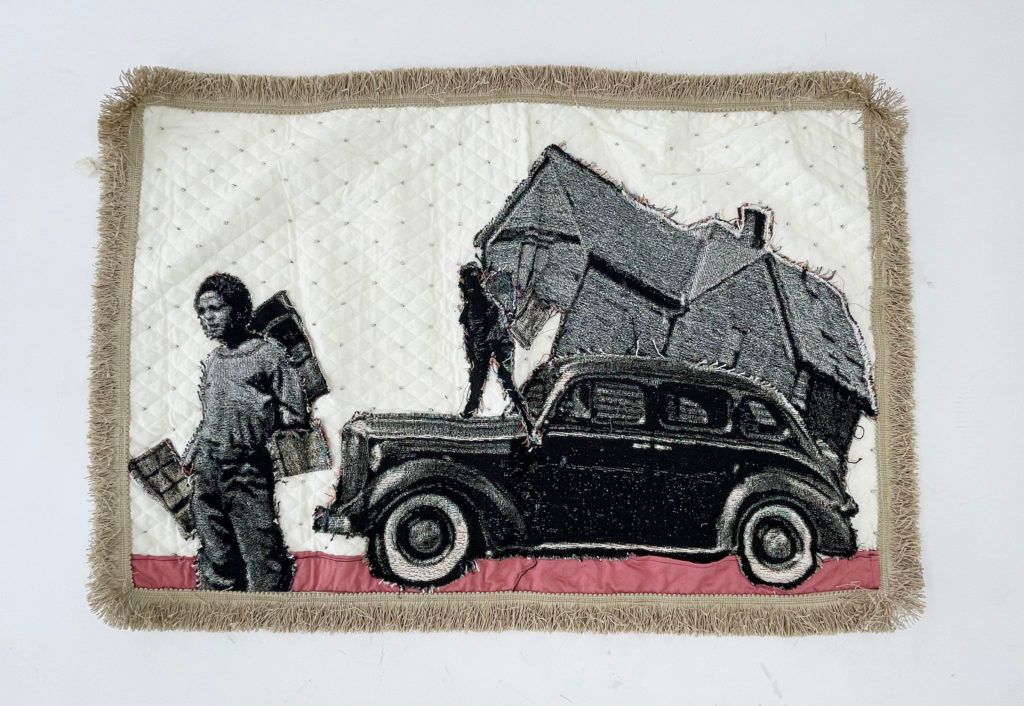

Hunter found black-and-white images of Detroit’s Black Bottom neighborhood shortly before its destruction, and had the images digitally woven by a jacquard loom. She removed the people from those images and placed them on brightly colored backgrounds, some filled with trees and flowers.

“With this work, I am attempting to lay the promise of ‘The Garden of the West’ next to the 1950s destruction of Black infrastructure, and the contemporary resilience of Black Detroiters to find a way through,” she said in her artist’s statement.

Hunter intends to keep the erasure of Black history as the focus of her art, no matter what form it takes. “We are often asked to show up, to help out, to give what we can. I’m asking that we remember,” she said in the Shaker Historical Society interview. “Remembering is an active thing we must do in order to not forget the past, and the way that we can combat erasure together. As long as someone remembers, then we as a society will not forget.”

Hunter’s exhibition was sponsored by New York State Council on the Arts,Nelson B. Delavan Foundation Part A, Cayuga County Convention and Visitors Bureau (Tour Cayuga), and Bartolotta Furniture. Support for this program is also provided by the City of Auburn’s American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) allocation of funds to support the City of Auburn Historic and Cultural Sites Commission’s Harriet Tubman Bicentennial project with a goal of boosting the recovery from the pandemic for the tourism, travel, and hospitality industry.