Sarah Bond traces her artwork inspiration to a slave in Kentucky

For artist Sarah Bond, quilting is more than just picking material, cutting it into geometric shapes, and sewing them together. Much more. With every selection, with every stitch, she is bringing her foremothers back to life.

“That’s one of the things I like about quilting, that these women are still alive through my work,” Bond said. “That this particular part of their lives, quilting, prevails in me.”

Bond traces her fiber art heritage to her great-great-grandmother, Jane Arthur Bond, who was born in 1828 as a slave, as well as three other quilters in her family. Her exhibit, highlighting the impact her ancestors’ quilts have had on her own work, will run June 12 to Aug. 7, 2021, at the Schweinfurth Art Center in Auburn. She will also give a free online talk about her family’s quilting history and influence, “Modern Quilts from my Grandmothers,” at 6 p.m. June 19, 2021, as part of the Schweinfurth’s Juneteenth celebration.

“I think quilting is in my blood,” she said. Her family history backs up that assertion.

Jane Arthur Bond was given as a wedding present when Belinda Arthur, the daughter of the family that owned her, married Preston Bond. “Preston, as was the fashion, took his pleasure with Jane when his wife was pregnant, so she had at least two sons by him that I know of,” Sarah Bond said. “James was born in 1863, Henry in 1865.”

Jane later went to work for Preston’s sister, Rebecca Bond Routt after the war. Rebecca and Jane made many quilts together, as Rebecca’s daughter recounted in her journals. “That’s how we know about the quilts, because she wrote about them,” Sarah said.

Henry, Bond’s great-grandfather, was the first member of the family who was born a free person. He married Anna Gibson Bond, another quilter who also taught school and raised 10 children. However, Sarah feels the closest connection to Louvinia Clarkson Cleckley, her great-grandmother on her father’s mother’s side.

“My great-grandmother Louvinia was born in 1858,” Bond said. “She made lots and lots of quilts. Louvinia had two daughters, my grandmother Rosabelle and Bertha, and there seemed to be some rivalry between them. When Louvinia died, Rosabelle went and got all the quilts before Bertha could get there. Because of that, I have a lot of Louvinia’s work.”

Sarah Bond grew up with Louvinia’s quilts on the family’s beds, but she didn’t know that at the time. In 1979, she decided spontaneously to make a quilt with scraps of fabric from clothes she had made.

“My mother came in and said, “What are you doing?’” Bond recalled. “And I said, ‘I’m making a quilt.’ And she said, ‘Why?’ And I said, ‘I’m not sure, I just need to.’ I did this before I knew my history. I knew we had quilts and I assumed someone made them. Then my father told me later on that the quilts on our beds were Louvinia’s.”

After her father died, Bond and her family found several more quilts in the basement, “which were still hiding from Bertha, apparently,” she quipped.

Much of Bond’s work, especially in the last several years, has been centered on Louvinia’s pieces, particularly her Lone Star quilts. “I’ve been doing a lot of work reconstructing and deconstructing these Lone Stars, partly as a creative exercise, partly as an homage to Louvinia,” she said. “It wasn’t until I started working on the Louvinia project that I realized she was born in 1858, I was born in 1958, and here the two of us are making work a century apart.”

Bond has made Lone Star quilts, a traditional pattern that features a large, eight-sided star made up of diamond-shaped fabric, as well as many variations on the Lone Star. Her inspiration might be traditional, but her take on it is definitely modern.

“I did an inverted Lone Star, where the points instead of pointing out, point to the center,” she said. “I did a lateral Lone Star, where the blades of the star are placed across the quilt instead of focused in toward the center. I do a quilt that I call Diamond Stair Step, where the same strips of diamonds you see in the Lone Star are separated and laid across the quilt, and they change direction. I do one also called Diamond Chain Link, where the diamonds are separated. They are still in line but not in blades like in a Lone Star. Then there are some where I separate the diamonds out.”

Bond teaches classes on all of these techniques, and she will be teaching a two-day online class called Making Modern Medallions through the Schweinfurth this summer.

There’s another quilter in Bond’s family history that has also been an inspiration. Ruth Clement Bond, the wife of Jane Arthur Bond’s grandson J. Max Bond, was a social activist who designed quilts that were commentaries on the situation of black people in America.

Ruth’s husband, Max, supervised the then segregated black workers on the Tennessee Valley Authority project in the 1930s. Ruth worked with the women, and designed quilts for the women to sew. One of those quilts, “The Lazy Man,” was selected as one of the 100 most important quilts of the 20th Century.

“I knew Ruth,” Bond said. “I saw her in 1996 at a family reunion. Even though she was in early stages of dementia, she remembered this (quilt). It was nice to be able to talk to her about what she had done in 1934 and the women she had worked with.”

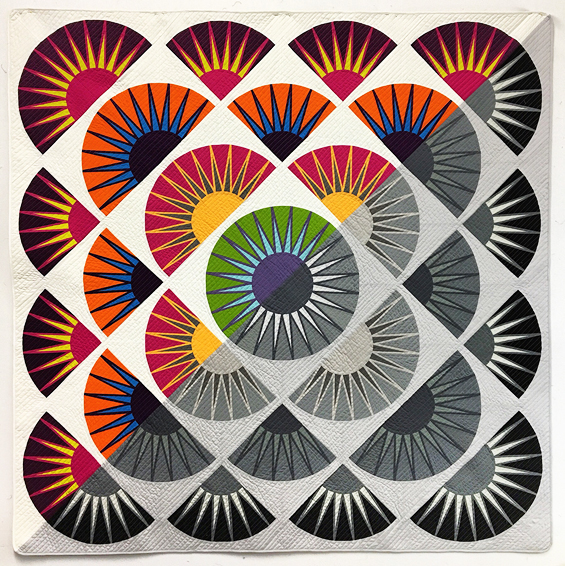

Ruth’s activism inspired Sarah to create “Shadow Liberty,” (above) a quilt that transitions from brightly colored rays to grayscale rays. “The point of that one is that liberty in this country is something that is different depending on who you are,” she said. “Although it may look the same, and if you squint your eyes and don’t want to see it, you might not see the difference. But if you look, you see it. We can all see it.”

Bond also volunteers with the Social Justice Sewing Academy and the group’s Remembrance Project, which makes quilts for the families of people who have died from violence. “(Quilting is) an art that has grown up in the context of people’s lives,” she said. “This material is made for and lives with people. I feel that in some ways, they absorb something about the lives of the people who live with them. The quilts are about the maker, the medium, the people who coexist with them, and the stories they pass on.”

The Schweinfurth Art Center’s programs are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Gov. Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.

Bond is teaching a two-day online quilting workshop, Making Modern Medallions, July 31 to Aug. 1. Link here for information and to sign up.