Four CNY artists featured in Schweinfurth’s “In Person” exhibit

The artists all show people or stand-ins for those no longer with us

The Schweinfurth Art Center’s fall exhibit “In Person” centers on people, whether it is the external stories implied by John Fitzsimmons’ large-scale figures, the internal self-examination of Lacey McKinney’s work, the relationship people have with animals explored by Donalee Peden Wesley, or the loss of a relationship after Holly Greenberg’s husband unexpectedly died.

Each examines life and death, grief and fear in an exhibit that brings together four Central New York artists whose focus complements each other, following a year like no other, when the world was brought to its knees by a microscopic virus.

“While many of these works were created prior to the COVID-19 global pandemic, the collective trauma of the previous year reframes the human figure,” said Schweinfurth Program Director Davana Robedee. “How can we move forward without placing the weight of this past year on everything we see?”

The show is on display through Oct. 9, 2021, at the Schweinfurth Art Center, 205 Genesee St., Auburn. Admission is $7 per person, or $12 for a joint admission ticket with the Cayuga Museum of History & Art. Visitors must wear masks.

Here are the artists talking about their work and how the pandemic has influenced it.

Working through loss

Fayetteville artist Holly Greenberg offers four larger-than-life drawings of items formerly owned by her husband, sculptor Timothy S. Brower. He died in 2017, leaving a studio full of his work, materials, tools, and equipment.

“At the time, I wasn’t sure if or for how long I might be able to keep all of his belongings; I feared that there might come a day when I would need to move and sell these large pieces of equipment,” Greenberg said. “I thought I should keep a record of them, some documentation so that his sons could retain a record of the things that had been so important to their father’s work.”

One day, Greenberg was inspired to draw the Eames chair that her husband used to sit in. “Without any planning, I grabbed an old bottle of India ink and pieced together three pieces of printmaking paper I had lying around to form one larger sheet, and started to paint,” she said.

“When I saw it come to life on the page, this empty chair, black and still, like a never-ending void, I realized that it resonated with the feeling of his absence. I then continued with the series, this time with large rolls of Arches watercolor paper.”

Next Greenberg drew her husband’s bicycle. “This was an important item for my husband,” she explained. “He had it custom built for his specific dimensions and paid for it using money he received in an insurance settlement from an accident at work when he cut off his finger on the table saw. He loved this bike and riding it was the one place he said he felt things were all right in his world.”

The illustration shows a bicycle lying on its side, seemingly forgotten – which is intentional. “He never would have left it lying carelessly on its side like this,” Greenberg said. “It shows a haste, a discarding, a quick departure. Much like his death.”

Greenberg has five pieces in her “Remains” series, of which the Schweinfurth is exhibiting four. She said she is currently working on a sixth piece, which shows her husband’s Carhartt jumpsuit.

She is also working in ceramics, using the new-to-her medium to explore the cycle of birth, death, decay, and rebirth. It’s a topic she feels strongly as she has had to survive the loss of her parents and in-laws in the span of two years following her husband’s death.

Her experiences have “perhaps helped me digest all the death we have experienced during COVID,” Greenberg said. “I seem have an underlying inkling that everything that lives must die; this is the cycle of all life, every plant, every insect, every animal.

“It’s the emotions of the living that are most distressed after a death of a loved one,” she continued. “That stress can destroy you if you let it. Creating these works, talking and writing and reading about life and death, have helped me stay vital in the land of the living.”

Artist, and an activist

Donalee Peden Wesley’s drawing show people in various poses near or sometimes surrounded by animals: Wolves, birds, bears, and more. But her art has a purpose: focusing attention on the treatment of animals.

“I would like my work to shine a light on how we interact with animals that share this planet,” she said. “Furthermore, I like to present certain practices or treatments that are inflected upon animals. I hope it might make the viewer aware of how horrible some of these treatments and practices are.”

You can learn what those practices are by reading the titles of her artworks: “Better Living Through Chemicals,” “Wet Market,” and “When They Go, They Are Gone, You Can’t Bring Them Back.”

Other pieces are evident from the image itself: A man cowers in fear in a coffin-like box, surrounding by wolves. “This fear is unfounded and based on fairy tales of the ‘big, bad wolf’,” Wesley said. Yet humans have posed the greatest threat to wolves, some species of which remain on endangered species lists.

Another piece, “The Stain,” shows two men holding a wrapped, body-shaped bundle with a bright red blotch on one area. In the background is a gray fog of animal images, including cats, dogs, and farm animals.

The piece “is about ghosts that haunt,” Wesley said. “It could be addressing going meat-free or at least know what conditions in which the animal was raised, getting rid of factory farms, thinking about where your clothing comes from. Now, with all the problems with climate change, we all will have to start thinking about our food supply.”

During the pandemic, Wesley was happy to see the rate of animal adoptions rise, but she was also worried. “At the same time, I worried they were only thinking of a temporary situation, not a forever home” she said. “Animals are a big responsibility and should never be acquired without doing some research and prep.

“I would like to see a course in animal care before someone takes an animal home,” she continued. “I would also like to see all these pets shops stopped from selling animals; most come from puppy mills, some birds are taken from the wild, along with reptiles. Animals should not be kept in the circus, forced to do stupid tricks, and roadside zoos, I could go on and on…”

Reimagining personal space

Lacey McKinney’s works examine value systems and gender expressed through collages.

“My art making process is of a way of thinking through my own experiences of being in the world,” said McKinney, of Liverpool. “Most of my work explores what it means to be a woman and how physical forms are developed over time from the intertwining of cultural constructs and biology.”

Some of them – paintings and photographs – are easy to recognize. But others require a close look to discover eyes, lips, and noses almost hidden among the painted strips of PVC or polyester film. That’s intentional, she says.

“The figurative representations are abstracted, cut up, and collaged, or made to be illusions of physical collages to show fragmentation and deconstruction,” McKinney said. “I am most interested in collective experience and interconnectedness through difference. For example, how one person’s story can act as a mirror to a sea of many stories.

“Collage also allows me to show vibration, discord, and movement, all of which act as analogies for the beauty and discomfort of bodily existence,” she added.

The pandemic hasn’t altered her work, although it has given her more time to focus on it. “The temporal nature of mortality is something that has always been inherent in my practice,” McKinney said. “Contemporary events are another reminder of the need to pull back and take a holistic look at the larger connections playing out between all living things.”

Telling visual stories

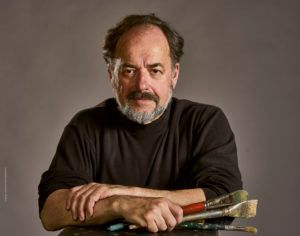

John Fitzsimmons made the most important decision of his art career four years ago, when he decided to focus on figurative paintings.

“I decided that I had to pick a direction and stick with it,” the Syracuse artist said, “so I pulled out all the paintings in my studio and spent a lot of time looking at them. When you allow yourself to change directions, it is easy to do that instead of maintaining your attack and breaking through whatever barrier is in front of you.”

Why the figure? “Everyone responds to the human image; it’s us!” Fitzsimmons said. “And as a subject, it offers infinite possibilities, from a formalist to a narrative basis.” And narratives are what he aims to capture in his large-scale paintings.

“My work implies stories, but they are stories than can only be told with pictures,” Fitzsimmons said. “That’s what I’m looking for in my painting, to get to that point where it’s not literal; it’s telling a story, but it cannot be expressed verbally. It can only be expressed by an image.”

The story was easier to spot in his earlier work. An observer can easily read a face contorted in anger or the action of a man – the artist – cupping his hand to his ear amid a faded background, perhaps a nod to his loss of hearing in both ears when he was a young child. However, his more recent paintings don’t telegraph the person’s mood. A middle-aged model stares into space in several pieces, her expression showing her deep in thought.

For one piece, “Four Women,” the key to understanding the story is knowing what was happening when it was painted in 2020. “I painted that last April and May during the height of COVID anxiety,” Fitzsimmons said. “No one really knew what was going to happen. I felt like I was living in a dystopian novel and recalled that Botticelli painted ‘Primavera’ and other works during the time of plague.”

The Schweinfurth Art Center’s programs are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Gov. Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.